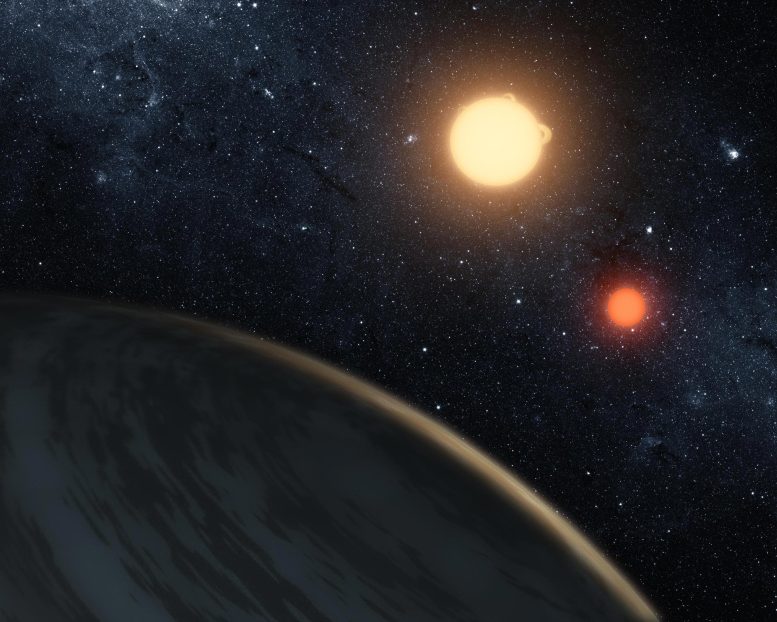

Vue d’artiste de Kepler-16b, la première planète connue à orbiter définitivement autour de deux étoiles – la soi-disant planète annulaire. La planète, visible au premier plan, a été découverte par la mission Kepler de la NASA. Crédit : NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

L’étude prouve que les télescopes au sol peuvent rechercher des planètes avec deux soleils.

Les astronomes ont utilisé de nouvelles technologies pour confirmer la vraie vie de Tatooine, la planète fictive avec deux soleils qui abritait Luke Skywalker dans « Star Wars ».

La planète Kepler-16b est à environ 245 années-lumière de la Terre et est une géante gazeuse de la taille de[{ » attribute= » »>Saturn. Scientists already knew that the planet existed, but in a recent study, an international team of astronomers explained how they successfully applied a technique that hadn’t been previously used to observe a planet orbiting two stars.

“It’s a confirmation that our method works,” said David Martin, co-author of the study and NASA Sagan Fellow in The Ohio State University’s Department of Astronomy. “And it creates an opportunity for us to apply this method now to identify other systems like this.”

The technique, called the radial velocity method, has long been used in astronomy. (The first planet ever found around a sun-like star was found using radial velocity – and was found using the same telescope astronomers used to find this one.)

The radial velocity method involves analyzing the spectra of light produced by the stars. Astronomers gather spectra data through telescopes on the ground – in this case, from a telescope based in France, the Observatoire de Haute Provence. That spectra data graphs into a line, but the line “wobbles” as the planet orbits around the two stars, producing a shaky line in the spectra of light. The wobble indicates a planet is there, and astronomers can use it to derive a number of other pieces of information about a planet, including its mass.

Measuring radial velocity is, Martin said, among the best tools astronomers have to identify exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system. But until this study, astronomers had not been able to use it to find planets outside our solar system that orbit two stars.

The study was published this week in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

In the past, such planets – known as circumbinary planets – were identified by monitoring when one star passed in front of the other. That method, known as the “transit method,” has identified 14 such planets, including Kepler-16b. The first confirmed circumbinary planet was described in a paper in 2011; others have followed. But until this paper, none had been found using radial velocity.

“What people had faced was that having two sets of spectra from two stars makes it really tricky, and people were struggling to get enough precision to see the wobble caused by the planet,” Martin said. “And we got around that by making a survey of systems with two stars that orbit each other where one star is big, and one is quite small.”

The survey, called Binaries Escorted by Orbiting Planets, or BEBOP, was established specifically to search for planets like this one.

One of Kepler-16b’s stars is about two-thirds the mass of Earth’s sun, and the other is about 20% the mass.

Astronomers had been watching this system since July 2016.

Proving that measuring radial velocities can identify planets that orbit two stars, Martin said, opens the door for the technique to be applied more broadly. That is important to astronomers for a number of reasons, but a big one is that planets that orbit two stars tend to exist at a distance that would make them good candidates for life.

“These planets are frequently found in the habitable zone, at a distance from the stars where you would expect to find liquid water,” Martin said.

Kepler-16b, which is made primarily of gas, is not likely to be a candidate where life could be found, Martin said. But using the radial-velocity method could help astronomers find other similar planets.

Reference: “BEBOP III. Observations and an independent mass measurement of Kepler-16 (AB) b – the first circumbinary planet detected with radial velocities” by Amaury H M J Triaud, Matthew R Standing, Neda Heidari, David V Martin, Isabelle Boisse, Alexandre Santerne, Alexandre C M Correia, Lorena Acuña, Matthew Battley, Xavier Bonfils, Andrés Carmona, Andrew Collier Cameron, Pía Cortés-Zuleta, Georgina Dransfield, Shweta Dalal, Magali Deleuil, Xavier Delfosse, João Faria, Thierry Forveille, Nathan C Hara, Guillaume Hébrard, Sergio Hoyer, Flavien Kiefer, Vedad Kunovac, Pierre F L Maxted, Eder Martioli, Nicola J Miller, Richard P Nelson, Mathilde Poveda, Hanno Rein, Lalitha Sairam, Stéphane Udry and Emma Willett, 25 February 2022, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stab3712

Martin’s portion of this work was funded in part by NASA.

« Drogué des réseaux sociaux. Explorateur d’une humilité exaspérante. Nerd du café. Amical résolveur de problèmes. Évangéliste culinaire. Étudiant. »